1899-1924:

Young days and education of Kosta Hakman

Tuzla, Sarajevo, Prague,

Vienna, Krakow

Kosta Hakman was born in Bosanska Krupa, on May 22nd in 1899, as the third child of Mihailo Hakman, a local judge and Darinka Đurić, a teacher.1 He finished elementary school in Tuzla, a town of approximately 2.500 inhabitants, which was an important administrative, cultural and religious center of Eastern Bosnia at the beginning of the century.2 In 1908 he started attending the Grammar School in Tuzla, thought to be one of the best schools in Bosnia at the time, and also known for its liberal ideas nurtured by both professors and students.3

With neighborhood children, Tuzla, 1913. Hakman standing in back, left.

The boy „of enormous height and brilliant intelligence“ was soon noticed not only for his „gift for painting“,4 and, as an excellent student, his talent for foreign languages, but also for his consciousness of „national belonging“, which in his early years already brought him in touch with the political organization at school, one that was affiliated with the movement „Mlada Bosna“5. After the assassination in Sarajevo in 1914, fifteen-year old Kosta Hakman was arrested and convicted. He served his ten-month prison sentence in Bihać. After being released Hakman continued his violently interrupted schooling in Tuzla, from 1915 to 1917, when he was drafted into the army service, and then, when the war ended, in Sarajevo, where he completed the First Male Grammar School in 1919.

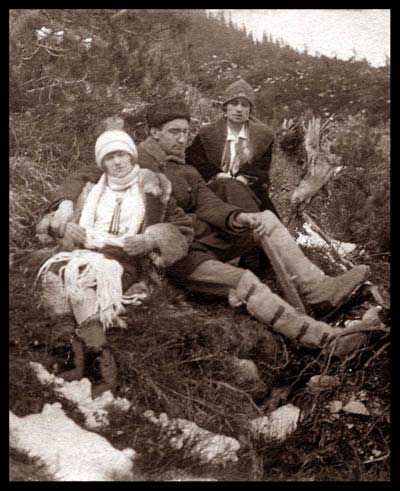

With colleagues in Poland (sitting beside Hakman is Hana Rudska).

Due to the lucky circumstance that he happened to be in Sarajevo in the autumn of 1917, he had the opportunity to visit the exhibition the exhibition in the great hall of the Country Government where the work of all the most well-known painters from Bosnia and Herzegovina at the beginning of the century was displayed.6. The encounter with these works of art crucially influenced his decision to become a painter, which he dreamt of in Tuzla where the influence of his teachers infected him with the beauty of artistic creation. Therefore, immediately upon his graduation, he sent the publishing house in Sarajevo, „Prosveta“, a letter of the following content: „Immediately after the overturn ... I requested a scholarship for the Art Academy, since I completed the necessary previous education with a private professor. The secretary of „Prosveta“ at the time promised me, and also recommended, that it would be much better if I passed my graduation exam first. Since I intend to become a painter regardless of whether I graduate or not, but I followed his advice nevertheless... thinking that this would assist me in the matter of the scholarship ... Now I am forced to start my studies immediately, without the scholarship, in order to prepare for my introductory exams. Therefore I must ask the Managing Board of „Prosveta“ to grant me assistance in the amount of 500 crowns since I travel to Prague on the 23rd of this month“.7

With the financial assistance that he did receive, though only 300 crowns instead of 500, Hakman arrived in Prague in August of 1919. After successfully passing the admittance examination, he became a student of the Academy of Fine Arts (Academic vytvarnich umeni) in Prague. He was enrolled in the preparatory class of professor Vlaho Bukovac as a „Serb of the Orthodox Christian faith“.

Although it did not have the reputation of the academies in Munich or Vienna, The Prague Academy was one of the more important European centers in which, since 1897 when Ivan Vavpotič from Ljubljana came to study there, more than a hundred artists from all our regions received their education. In the period immediately after the war, from 1919 to 1923, there were more Yugoslav students in Prague than ever before, and they enjoyed great privileges—partly due to the fact that they came from a »fellow« country, Yugoslavia, and also thanks to Vlaho Bukovac8 from Cavtat, who was one of respected professors on the Academy. However, the teaching based on a traditional, academic approach did not appeal to our students and many of them left the Academy after the first year of studies. But although the studies at the Academy did not fulfill their expectations, the stay in for Prague, where „everything painted in Paris on Monday had a national edition on Friday“, was of multiple use to our students. If we mention but a few of exhibitions held in Prague even before the first World War—The Exhibition of Auguste Rodin (in 1902), Edvard Munch (1905), French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists (1907), Antoine Bourdelle (1909), »Gallery of the Independent“, Matisse (1910), Pablo Picasso (1913), Archipenko, Brancusi and Duchamp (1914); — we can conclude that our students experienced their first direct contact with Europe9 in Prague.

Kosta Hakman spent two semesters at the Prague Academy: the first he barely finished successfully, and failed the one. Discouraged by his personal failure, and dissatisfied with the studies at the Academy and the pedagogic approach of professor Bukovac, whom the painter Konjović „accused“ of teaching his students „the use of superficial effects“!10, Hakman decided to leave Prague.

His first summer vacation in 1920 he spent in Tuzla, together with his friends from the Grammar School, who also came home for the holidays when the academic year ended. Fascinated by their stories about the richness of the museum collections in what was until shortly before then the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, Hakman decided to continue his studies in Vienna.11 Since he was without the necessary means, he wrote once more to the Managerial Board of „Prosveta“, asking them for „assistance by way of traveling expenses, so that he could continue his studies.“ Thanks to the assistance that he was again granted, Hakman was already able to depart for Vienna in the autumn of 1920. He enrolled in the private school of the painter Frühlich, where classes were held in an informal manner: students painted according to their personal affinities, while the only corrections made were on errors of a technical nature12.

In the years immediately after the First War, Vienna lived off its old glory from the beginning of the century when, as one of the most influential centers of the European Secession, it gathered the most famous artists such as Gustav Klimt. Except for the individual endeavors of several progressive artists, one of whom was young Oskar Kokoschka, painting in Vienna during the post-war period stagnated—even worse, vegetated with no advance in the field of national art and more widely accepted initiative to adopt the modern movements that were arising in the neighboring countries. In such a climate the Viennese artistic circles remained closed for foreign students, who therefore felt isolated.

Soon after his arrival Hakman realized that the situation in the Austrian metropolis was not quite what he wanted either, although the abundant museums of Vienna gave him the chance to enrich his formal education. His disappointment was all the greater for having another unsuccessful, uncompleted school year behind him, and for the weakening of his reputation at „Prosveta“. That is why he had left Vienna before the end of the school year, intending to ask the Regional Government of Bosnia and Herzegovina for a regular monthly scholarship, to be able to study continually. This time, he had decided to study in Poland, influenced by his friend Marcel Schneider, a student of philosophy.13

Thanks to the regular scholarship that he received in the autumn of 1921, Hakman went to Krakow and passed the admittance exam at the Academy of Fine Arts (Akademija sztuk picknych). He enrolled in the class of professor Stanislaw Weiss.14

In the class of professor Stanislaw Weis.

The cultural climate in Krakow was more favorable for our students, more hearty, and the Academy in Krakow, which had already nurtured one generation of artists from Bosnia,15, was pedagogically felt to be more progressive than the academies in Prague and Vienna. This opinion was certainly contributed to by a „new generation“ of professors a more liberal attitude towards the students, both at school and elsewhere, since they befriended the students and exhibited16 together with them.

In the period after the First War the Academy in Krakow attracted the most famous Polish artists from the first half of the twentieth century—both the strictest colorists and artists who based their analyses of form on the experiences of Cubism, Futurism and Expressionism. Colorists studied the art of Cezanne—in order to be more successful at creating with color that radiates light, proving their devotion to French art by founding the „Paris Committee“ (Komitet Paryžski), while others formed their artistic pictures as „unlimited succession of objects“ (Hvistek) or as „records of the relations between the elements“ (Vitkiewitch), and gathered in a group named „Form“ (the so-called Formists), they played an important role in the development of the Polish avant-garde—the Constructivism.17

There was a hearty atmosphere both in and out of the Academy (Hakman second to the right).

Hakman's professors Stanislaw Weiss and Jacek Malčewski18 belonged to the group of Colorists and were the main promoters of post-impressionism in Poland. In their theories Hakman found not only the confirmation of his own artistic affinities but also the opportunity to master the art of painting, above all to delve into the mysteries of impressionistic landscape painting, which was the most frequent theme in the works of his professors. The success of the Academy in Krakow was certainly contributed to by one of its departments—The School of Landscape Painting founded in village Poronin, not far from Zakopane, at the beginning of the century, where the students were led by professor Kamocki19 to apply their theoretical knowledge, acquired at the Academy.20 In such working conditions Hakman, as a third-year student, was already certain that he had found his own painting, and convinced in the truth of the said, wrote into his index: „There is no line, no form, there are only contrasts ... not in black and white, but in coloristic impression.“

Hakman worked hard in Poland, which is vouched for by the great number of paintings he then created and awards that he received during his studies. It remains unclear why the Regional Government revoked his scholarship in 1923. Afraid for the future of his work, he addressed the Sarajevo „Prosveta“ for the third time with a request „to assist him once more now that he was in such a difficult financial situation, with a loan, so that he would be able to complete his studies.“ Hakman finished his studies in June of 1924 with excellent marks. He was awarded two prizes at his final examination—the first for landscape painting and the second for the painting of acts, of which a note was made in his index. Upon receiving his diploma, after a short trip to Italy (1924/25), he briefly returned to Bosnia; and then went to Belgrade, which became the destination of may artists from various parts of the new country after the war.21

1. Father, a descendant of Polish immigrants, mother, Serb origin, from Sarajevo. There were six children in the family: Mihailo, Stefan, Kosta, Nikola, Jelena, Zora.

2. His teacher was Veljko Čubrilović.

3. Grammar school was for boys only. In 1910, a High school „Zadruga Srpkinja“ for girls, was opened with help of rich citizens of Tuzla. In 1916, the school was named a State Crafts School.

4. His painting gift was noted by a drawing teacher, Sava Popović-Ivanov, a painter who studied in Vienna and Munich and, after he finished his studies, came back to Bosnia and had the reputation of a very „successful pedagogue“.

5. Members of the organization already were: his brother Stefan (the oldest Mihailo died in Austro-Hungarian prison), Mladen and Sreten Stojanović, Boža Tomić, Borota etc. See: Vladimir Dedijer, Sarajevo 1914, Prosveta, Beograd, 1966, p. 581, and Nikola Trišić, Sarajevski atentat u svijetlu bibliografskih podataka, Sarajevo, 1964.

6. Since in August of 1917 a Department of Country Government for Science, Art and Literature was established, artists were ordered to take part in the exhibition. Fourteen artists from Bosnia and Herzegovina, educated in Prague, Vienna, Munich, Budapest and Krakow, took part in the exhibition, as well as six foreigners, with an explanation that they are „in the country service and are not just mere foreigners“.

7. From materials of „Prosveta“, being prepared for printing. Materials were collected and explained by Danka Damjanović, a curator in Umjetnička galerija BiH in Sarajevo.

8. Hakman was persuaded to go to Prague by his professors, mostly by prof. Švrakić, who had studied there, together with Branko Radulović and Pero Popović. The tuition fee was lower for our students, and poorest among them received assistance from foundations at the Academy. That privilege was abolished after death of Vlaho Bukovac in 1922.

8. Young critics who gave their contributions to intensive cultural life, were hastening their battle against inherited conservative attitudes. They were all grouped around „jednite vytvarnich umetniku“ (conservative), and around group „Manes“, which attracted artists with progressive ideas who laid out their opinions in a journal „Volne smery“. Our students were also on friendly terms with avant-garde artists—Špal and Kupka.

10. Dragoslav Đorđević, Katalog retrospektivne izlože Mlana Konjovića, Muzej savremene umetnosti, Beograd, 1975.

11. Sreten Stojanović studied in Kunstgewerbeschule, in the class of professor Hanak.

12. Dragutin Mitrinović and Ivo Šerment enrolled in the school with him. Milan Konjović, Mihailo Petrov and Sava Ipić joined them later on. The school was in the center of Vienna, in Anna Gasse Street.

13. The parents of Marcel Schneider came to Bosnia from Poland. Since he spoke Polish, Schneider helped Hakman get in touch with the Academy in Krakow and wrote applications for the admission exams for all other students.

14. Wojciech Stanislav Weiss (1875-1950) studied under the painter Wichulowsky.

15. Jovan Bijelić, Roman Petrović, Petar Tiješić, Muhamed Kulenović, Mihailo Timšić studied in Krakow before the First World War. Apart from Hakman, in 1921, Dragutin Mitrinovć, Ivo Šerement, Sava Ipić and Milan Četić also came to the Academy.

16. The Academy was reformed in 1895. Young artists, educated in Paris, came there to teach students.

17. See: Joanna Pollakowa, Poljsko slikarstvo između ratova 1918-1939, Jugoslavija Public, Beograd, 1982 and T. Dobrowolski, Nowchzesne malerstwo I, II, Warszava, 1960.

18. Jacek Malčewski (1854-1929), a painter.

19. Kamocki Stanislaw, (1875-1944), a student of Stanislawski and Wichulkowski.

20. School of landscape painting founded in 1900 by painter Jan Grezegorz Stanislawski, (1860-1907), who based his teaching method on the „subtle colors, ambience, atmosphere, fluttering and light transparency of shadows.“

21. They were also coming to study there, although the Artistic School had no status of state school.

©2003-2004 Project Rastko, TIA Janus (Belgrade), Hakman

family and other copyright holders.

No part of this site can be used or distributed without permission.