1925-1940:

Belgrade, Paris, Belgrade

Kosta Hakman and painter Dragutin Mitrinović, Belgrade, 1938.

Hakman arrived in Belgrade in 1925, when many young artists returned from schools in different European countries, bringing with them the ideas and principles of new and avant-garde tendencies and schools, making their activities seem like a „hot volcanic movement“ (Sreten Stojanović). However, the ideas of „the anarchic and decadent young generation“ were not accepted in the Belgrade community interested in gaining economic power and oriented towards obtaining political positions. And so it was obvious during the first postwar years that the cultural climate in the town was not supported by material prosperity and that „our richest people, tradesmen and industrials, were not among those of that bought works of art“.22 Therefore the initiative of a certain number of citizens to undertake measures for the economically strengthened Belgrade „to become the cultural center of the state, first of all to open a gallery in which artists would gather and exhibit their works of art“23, was welcome.

In such a climate Hakman held his first solo exhibition in December of 1925, in the hall of the Elementary School nearby the Congregation Cathedral. The exhibition was opened with a speech by the Polish consul in Belgrade, which gave the newspapers of the capital cause to describe the exhibition as „a fine example of Yugoslav and Polish friendship.“ In a review of the exhibited work the art critic of the daily paper „Politika“ wrote that the paintings had all the characteristics of the environment in which the artist studied, adding that „such typical Polish landscape and impressionism ... are not unknown to us ... for we already have several good artists who were educated there.“

Since the review did not mention with which paintings Hakman presented himself to the Belgrade audience, we can only confirm the judgment of the critic on the basis of several preserved paintings which we have reason to believe were exhibited then, for they are from the period before 1925.

These paintings by Hakman, created in Poland in 1924 or Bosnia in 1925, are mostly landscapes, characterized by strongly illuminated, decorative surfaces on which Hakman, using impressionistic vibrations, stirs natural light and develops a rich, light and dark, play of colored surfaces—not with the intention to cause dramatic clashes on the paintings but to give freshness and liveliness to the scene. Therefore the surface of his paintings, lit by rays of sunlight penetrating through leafy treetops and casting transparent shadows on the grass, radiates with an intensive light. Hakman builds the architecture of his paintings by coloristic plans, not insisting on the depth of space, but attempting to give the paintings a solid structure. That is why he constructs real scenes as a harmonic relation of horizontals and verticals, setting the focus at the top of the hill covering the horizon; thus, just as Cezanne did in his painting „Marronniers à Jas de Bouffan“, achieving the balance of the painting (Landscape from Poland). Such landscapes devoid of human figures have almost magic meaning, concealing within them elements of symbolism, so characteristic for Polish Impressionism and for the work of Hakman's professor Jacek Milcewski: rhythmic verticals of century-old trees whose elongated shadows spill vertically across the grass as their visual counterpoint, hinting at other realities and essences („for true, immortal art was and is symbolic“). This seems to be even more accentuated in winter landscapes where pink and violet are reduced to icy reflections of white, while the arabesques of bare branches, resembling a linear stylization, are traced against the grey sky (Snow-covered Landscape).

Snow-Covered Landscape, 1924.

Sometimes Hakman combines a yellowish-green palette with bluish-white colder tones to, in a succession of brush-strokes almost like fine weaving, define shapes and create the „noble“ atmosphere of a summer day. When in such a sunlit landscape, where human presence is only hinted at by objects for everyday use, the forms start to melt and blend, Hakman intervenes with short, firm brush strokes or with seemingly meaningless details, such as, for example, a wooden fence, to give firmness to the painting and balance to the composition (Still-Life in Landscape). The painting Self Portrait with Black Hat also contains a rich world of symbolism. The figure beside the window, reminiscent of Renaissance portraits, is painted in two thirds profile, representing a lad with a black, artistic, wide-brimmed hat, as a symbol of dedication to the artistic calling. In the background, there is a strong source of light, and new scene develops as if in a theater: a full spring landscape which by its fresh greenery announces a rich artistic harvest. Before us we have a young artist and his work as the inseparable unity of artist and art.

Due to the selling of a great number of paintings and the improvement of his financial affairs, Hakman realized his dream — to go to Paris for the first time.24 He stayed in Paris for four years, during which time he came to Belgrade only once, in 1927, to take part in the VI Yugoslav Exhibition in Novi Sad.

This large exhibition, held on the occasion of the 100-th anniversary of „Matica Srpska“ (Serbian literary and artistic association), was awaited with understandable impatience, for, as Boško Tokin wrote at the time, „representative exhibitions are rarely held that we do not have the opportunity to see a review of our artistic groups, we cannot compare them nor were we in the position to see the development of modern art.“25. When the exhibition was opened after grand announcements, the same critic concluded that the „general impression is favorable“, but with regard to the individual values of the exhibited works of art „must be less content“26. Hakman, who took part in the exhibition as a Belgrade artist independent of groups, displayed paintings with which he presented his work in Paris. Art critics at the time judged his paintings to be „among the better work at the exhibition“, concluding that his Paris paintings show „not only that he is deft at harmonizing color but also has talent for contemporary composition“.27

After the closing of the exhibition which was the reason for his brief stay in Belgrade, Hakman returned to France to prepare for his second exhibition in Belgrade, encouraged by the positive critics on his work.

While he was working in Paris the Belgrade environment experienced significant changes in the sense of promoting both national and international culture, mostly due to the activities of members of the Association of Friends of Art „Cvijeta Zuzorić“. Their endeavors brought about several cultural manifestations in Belgrade, among which were important exhibitions that were useful lessons for our artists.28 However, the most significant event was certainly the opening of the Gallery at Kalemegdan, on which occasion Veljko Petrović had much cause to say: „this first exhibition in our first Belgrade art pavilion ... is an indication of the proliferation of our modern art.“

Hakman held his second solo exhibition in Belgrade at the newly-opened Art Gallery at Kalemegdan, in November of 1929. With fifty exhibited works of art—paintings and aquarelles—he represented his almost four years of work in France. Most of the displayed work consisted of landscapes and critics mainly wrote about his „live, warm and almost lyrical feeling for nature ... for the fresh flickering greenery of spring fields and trees.“ He also exhibited several paintings of urban scenery, on the basis of which critics concluded that Hakman had searched more for „misery than for luxury, painting blind alleys“ in the streets of Paris. In their reviews of Hakman's exhibition critics concluded that „he does not present great problems to himself, but simply paints“, and one of them pointed out a characteristic of the painter expressed in his Self Portrait, that: „he also possesses character and sophistication in his views that deserves high commendation“29.

Since we are deprived of the critic's further comment on the work, we do not know which painting he had in mind, for during his stay in Paris Hakman painted two brilliant self portraits and the common feature of both is movement: on one the movement is represented by expressionistic gestures, on the other—by intimistic restraint.

Self-Portrait, 1928

The first to be created (in 1926) is a painting which has a special place in Hakman's artistic opus because of its proceeding based on postulates close to expressionistic poetics: a figure of potential expressive strength emerging from the movement of the body which, like a visual crescendo, grows into a powerful expressive gesture this stressing the harsh reality of everyday life. The expressionistic body movement is accompanied by a facial expression represented as the reflection of the psychological motivation of the gesture. The scene seems to describe the artist's life, turning it into a single dramatic movement („Self-Portrait with Accordion“).

The second painting created in 1928 discloses the miraculous power of the human figure to express itself without words, to be more eloquent with inner motion than with any speech. In the picture it is frozen, turned into an eternal, barely noticeable, suggestively announced movement, but sufficient to bear the burden of mysterious wondering. The background of that exquisite painting seems to announce a different essence: resolved in gradual, insufficiently defined cube forms and almost devoid of air, it seems more as a memory than the experience of a landscape seen (Self Portrait with a Cigarette).

We have an interesting article on this exhibition of Hakman's from the pen of Gustav Krklec, published in 1929. From the paintings of urban scenery he concluded that Hakman's talent was not just „pure painting talent“ but that „many poetical-social and bohemian-proletarian sparks“ were hidden within it, which, in his opinion, was significant, for Yugoslav painting was „rich and varied ... and all tendencies and forms were represented, and especially all schools, apart for the one that Mr. Hakman's talent inclines towards“.30

With Dragutin Mitrinović and Ljuba Ivanović, Paris, 1928.

Such a conclusion speaks of the humanistic component of Hakman's painting, which we can read from his individual creations.

Then we notice that objective reality was, to him, but the cause to express his world, to soak his work in warmth, to enrich banal reality with his emotion and transform it into artistic value. Only upon careful observation of his paintings do we see that beneath the almost uniform colors and seemingly light and silky structure of the painting lie an entire life and plastic world, in the depths of the texture. Those remote streets of the town suburbs, with human figures or without, are always colored with a „local tone“ and the dimension of a coating of time. Those are, mainly, simple stories about poor city quarters in which both people and nature vegetate. The pictures are created in a uniform palette of ochre, brown and olive-gray tones at short intervals of strokes, among which an intense green chord resounds from time to time. Slow brush strokes, sometimes melting into each other, only occasionally point out the earlier vibrations and are lit by a pearly glisten that shines from the warm harmony of the paintings (A Street in Paris, Cathedral in Moaux, Street Corner etc).

Pont Neuf , 1928

The painting Pont Neuf is of somewhat different tonality. Statically balanced, stabilized by the logical rhythm of details and the whole, the main and the marginal, the stressed and the unstressed. The composition if the painting reaches to the very bottom of the scene and like a document of the place and time reveals an area in which the life of a modern city pulsates—Paris with its boulevards, full of people and traffic. Similar to the „Avenue de L'Opera“ by Camille Pissarro, there are people walking in Hakman's paintings well but, instead of coaches they drive automobiles, that symbol of a new era. In this painting, which was created in a finely toned note of pinkish-grey, there are only a few stronger, more visible stains that, although seemingly accidental, contain within them the anecdote and symbolism of events.

As the third decade was drawing to a close, differences in the approach to works of art and their meaning were becoming more and more apparent among the artists in Belgrade. They categorized themselves as „traditionalists“ and „modernists“, and during the course of time, due to the practical need to step forward in unison and support each other, they formed associations—ideologically, in groups. So, apart from the already existed association—LADA (1904), the branch association ULU and the GRUPA UMETNIKA, which gathered not only painters and sculptors but also writers and musicians in order to „keep our artistic movement in closest possible connection with the artistic movements in great artistic centers“31, in the late thirties the group ZOGRAF was founded, the members of which believed that „we must not be a mere colony of French painting“32, as well as the group OBLIK, whose followers felt that „until we cure our European complex and learn to speak as Europeans we shall never be able to find that of value within us“33.

Both by his natural inclinations and his artistic direction Hakman belonged to modern flows, which is why he became a member of the group OBLIK as early as 1927, immediately after it was founded. However, he had only one collective exhibition with the group—their first exhibition at the Belgrade Art Gallery, held from December 15, 1929, to January 4, 1930.

The exhibition of the group OBLIK, which took on a leading role in painting circles of Belgrade soon after its formation, aroused great interest of both the critics and the public. In the speech with which he opened the exhibition Veljko Stanojević stressed that it was high time to establish „European criteria and constant contacts with the current sources of artistic creation... which is the founding signature of the group.“ The exhibition was followed by great number of texts accentuating that „these painters, first of all, wish to be honest and objective“, to „show a feeling for measure and harmony and a romantic love towards color“ and that „the group OBLIK is in reborn traditionalism, enriched by the experience of all revolutionary tendencies“34. It was also said on that occasion that of the exhibited work „the landscapes were best“, among which were two pictures by Kosta Hakman: Plaisance and Malakoff.

The painting Malakoff represented the artist at the exhibition in London as well, in April of 1970, when the Croatian Art Association lead by Ivan Meštrović put together a representative selection of Yugoslav art 35.

Of this exhibition, at the opening of which exhibition Branko Popović said that „our modern art ... is yet in its first zeal“, art critics in London noted that, regarding sculpture, „Yugoslavs are quite outstanding, for their national genius seems to be instinctive in that field“36, while the painting was described as „interpreter“ of that already seen in the world.

From the rich literature of the thirties, books, magazines and art critiques published in daily and periodical papers, we conclude that the cultural life of Belgrade was in strongly progressing during the fourth decade. Apart from the founding of a large number of cultural institutions, such as the Academy of Music and Academy of Fine Arts, the art critique was also rich and varied, brought by the most prominent intellectuals of the time. This was certainly contributed to by the reputable magazine „Umetnički pregled“ (Art Review), founded by the famous writer, art critic and erudite, Milan Kašanin in 1937. The pages of the magazine contained articles by writers, artists, art critics, philosophers: Ivo Andrić, Aleksandar Deroko, Svetozar Radojčić, Jovan Dučić, Isidora Sekulić, Stanislav Vinaver, Todor Manojlović, Predrag Milosavljević, Miloš Đurić, Branko Lazarević, Milo Milunović, Dušan Stojanović, Branko Popović, Pavle Vasić, Đorđe Mano-Zisi and many others. By the joint effort of young Serbian intellectuals, in the fourth decade Belgrade became a respected cultural center granted the organizing of important manifestations, such as, unsurpassed in artistic values, the exhibition „Italian portrait through the centuries“ ─ a center in which writers and artists with prominent positions in the history of European culture lived and worked.

Kosta Hakman entered the fourth decade as an already noted artist, who was characterized by Belgrade critics as a „typical representative of the painting of Belgrade“. The fourth decade encompassed the third and fourth phase of his work, marked by his considerate and formed mastership. On these paintings everything is thought through: uniformly created harmony, light, color and above all, perfectly balanced composition. Apart from regularly taking part in collective exhibitions, both at home and abroad, he also had two solo exhibitions during the thirties, in 1930 began teaching as well: first he taught drawing at the first grammar school for boys in Belgrade (1930-1935); and then moved on to the Technical University where, at the department of architecture, he became a professor of ornamental drawing skills and in aquarelle painting (1935-1940); in 1940 he became an associate professor at the Academy of Fine Arts, which was founded two years earlier.37 Hakman also worked hard to protect the interests of his class, for a better treatment of art and better relations between artists themselves. That is why, in March of 1930, he was one of artists who founded KOLO JUGOSLOVENSKIH LIKOVNIH UMETNIKA (Association of Yugoslav Plastic Artists), a group that had the aim to „unite all Yugoslav plastic artists of modern artistic views... to establish the closest connections with all Slavic artistic associations of similar views and to act with them towards developing the idea of Slavic brotherhood ... to fight decisively against any suppression of art, for the complete freedom of artistic creation and expression, against biased judgements in awarding artistic prices at collective exhibitions of artistic groups at home, bearing in mind that all of those groups have full moral responsibility for the artistic value of the work they exhibit“38. Since such a democratic concept and broadly defined program received neither the support of artistic groups nor the understanding of Belgrade artists, KOLO JUGOSLOVENSKIH LIKOVNIH UMETNIKA ceased to exist without having held a single collective exhibition nor celebrating its first anniversary.

From May to August 1930, Hakman was in Paris once more, working hard and preparing for his next exhibition in Belgrade. Hakman held this third solo exhibition together with Sreten Stojanović in February of 1931 at the Art Gallery at Kalemegdan. The joint exhibiting of two famous Belgrade artists aroused great interest. In comments on the exhibition as a whole it was noted that the impression was that the artists were still „wandering and searching for personal expression“ although „their qualities had been proven more than once.“ As for Hakman's paintings, the art critic of „Politika“ wrote then that they revealed the hand of an artist „of excellent school, with an unusual amount of feeling for tone and color and a spontaneous manner of expression“,39 „that the artist likes his colors to flicker“, that „the color shows complete freedom of elementary qualities“40, and that because the artist „senses color most directly“, he neglects the drawing, thus also exhibiting a „badly constructed portrait of Lj. I.“41

That painting of Hakman's, Ljuba Ivanović, testifies that the artist was never closer to the spirit of French painting of poetic realism, not only by the refinement of color but also by the select subject matter of interiors typical for the sensibility of French Intimists, Bonnard and Vuillard.

Studying the painting of Pierre Bonnard, one of the most significant representatives of Intimistic painting, John Rewald discovered that Intimists worked with lot of system, long and slow, on their paintings that reflected spontaneity and ease. Lead by a quote from a letter written by Bonnard in which the artist says that his first paintings were made „instinctively“, but that he created all others with much method, „for instinct that feeds method has an advantage over method that feeds instinct“, Rewald concluded that intimistic paintings were the result of very well thought-out work and that only careful observation will disclose that it „represents a certain scene and suggests new lines of thought at the same time“. Therefore their effect on the viewer is slow, gradual, and is primarily intended for living quarters, where „friendly eyes return to them again and again until every colored trace on the painting resounds with its own melody.“42

In the already well researched Yugoslav fine art from the first half of the twentieth century, Serbian painting between the two wars was studied particularly well.43 Carefully reconstructing that period of Serbian art, authors diversely covered the painting of the thirties, not only in the context of the development of fine arts but much more broadly, considering that period to be a time of strengthening of the Serbian bourgeoisie society, the prosperity of which was chronicled by the art of the Intimists.

The aforementioned portrait of Ljuba Ivanović was created in pure Intimistic technique, in finely shaded tones of warm brown. While the foreground is filled by a sitting figure presented with deliberately altered proportions, in a position suggesting certain deformations and shortenings, the background does not contain sufficient distance between planes, losing full orientation in space and the painting is constructed in Bonnard's manner of a flat view from „above“. However, notwithstanding the Bonnard-like associations, Hakman felt the whole scene as a „dimension of his own spirit“ and enriched the painting with his personal artistic expression. By well thought-out connecting of the main and marginal as „simple“ and „complex“ elements, he created a harmonious entity, both in composition and in tone.

A similar procedure but in a somewhat more developed scale of finely selected blue, green and brownish-violet tones was applied by Hakman to his painting A Girl with a Doll, thus implying the sonic values of the cycle „Children's Corner“. This gave a chaste intimistic scene layered meaning and the value of a visual essay on the magical world of children's fantasy.

Hakman certainly owes his extraordinary capability to give every painting the right „atmosphere“ to French art which he felt with the instinct of his artistic nature; art in which Bernard Dorival noticed an Impressionist destination in our century; a manner of adopting the experience of Impressionists who, following the principles of strict analyses in the desire to „grasp everything... even air“ on their paintings, traveled the furthest in complete portraying of nature. Among the many and diverse art tendencies in Paris, all of which had the same starting point of return to nature, Dorival singled out one movement neither active in theoretical disputes nor in the publishing of proclamations, which took on the leading role without great announcements. Followers of this movement were familiar with the views of Impressionism as a „subgroup of realism“, aesthetics based on „feelings“, as well as the experience of Cezanne, who „reached pure painting and found the eternal aspect of matters“.43

A perceptualist by artistic nature, Hakman could not rid himself of his obsession with motive. It hindered (or assisted) him to sacrifice the subject of the seen to the demands of Impressionistic dematerialization. Thus, with a subdued impressionistic palette, laying one stroke beside another, he managed to color every painting with a „poetic, realistic tone“, to paint reflections on water by selecting the appropriate brownish, blue, emerald tones and dosing the necessary quantity of light - glaring or soft; or to express the dimension of time in a landscape of century-old olive trees; but also, motivated by the feeling for the social value of the picture, to paint a figure with easy strokes, more as a need to record a moment from everyday life (Fisherman). However, Hakman experienced the most direct contact with nature when painting scenery, most frequently seaside landscapes, in which he found an inexhaustible source of inspiration.

„Fisherman“, around 1930

In his painting Landscape (Hercegnovi) from 1931 Hakman proved that he knew how to penetrate into the inner sense of motive and color it with appropriate „atmosphere“ without oppressing the real scene, which must exist before the act of creation as a model offered by nature. In an almost monochrome picture, realized in a modulation of soft shades of light, endowing every tone with the appropriate quantity of light, he developed a warm play of green tones and exquisite inner glow.

Hakman exhibited this painting at the IV Spring Exhibition of Yugoslav artists in 1932; the exhibition that some art critics described as „live and rich ... cultured and European in appearance“, where our artists „spoke out in the most modern and most European language“44, while others characterized it as „spiritual misery of Yugoslav art for the fourth time ... for the artists travel worn paths far from reality... while artists from Paris have a solid but conservative method with reactionary meaning“45, and which caused disruptions among the artists. Because of the decision of the organizers for famous artists to exhibit by invitation, without judging the work, the Art Gallery „Cvijeta Zuzorić“ invoked the wrath of those artists which were not referred to by this decision. „The organizer“, they wrote at the time, „has proven ignorance of the true situation in our contemporary artistic creation ... and yet has taken on the role of classifying our artistic values“47. On the other hand, the decision was welcomed by famous artists and Ivan Meštrović wrote that „such a procedure is the only real way of gathering all those artists that are truly capable of representing the entire contemporary Yugoslav art“48

The attempt of the Gallery „Cvijeta Zuzorić“ for the spring exhibitions to become truly Yugoslav not only lacked the desired result but also deepened the disruption among the already disagreeing Yugoslav artists. This became apparent the very same year, during preparations for a representative exhibition in Holland. Held in the City Museum in Amsterdam from September 24 to October 23, 1932, described by Dutch critics as, among other things, a „fine example of care for art“, the exhibition did not include all the artists whose work might have contributed to the impression about the complexity of Yugoslav fine arts in the thirties.49

During the thirties, Hakman regularly exhibited at Spring and Autumn Exhibitions and his painting was diversely evaluated by critics: from being „lyrical“ with a „pearly sheen“ to the opinion that „the has a clear expression with true artistic nerve flowing through him, without tricks and empty effects“, that his paintings are a „full artistic pleasure created out of pure feeling for painting and visual dimension“ to the conclusion that he was „a typical representative of Belgrade painting already well introduced to the audience“. On the occasion of his fourth solo exhibition, opened in February of 1936 at the Art Gallery at Kalemegdan, without official speeches but in the presence of a large number of „well known persons“, critics pointed out Hakman's „rather rare qualities in the domain of talent“, but also his „intellectual qualities“ showing a „greater natural intelligence and broad culture“. In the analysis of his exhibited works it was noted that some of his oil paintings were created as „oil sketches“, although, said the critic, „this is typical for aquarelles while oil colors require a base, just as a house requires a foundation“50.

However, due to just such a „sketch“ entitled Hercegnovi, from 1933, we can conclude that in oil painting as well Hakman knew how to realize a paining of aquarelle transparency refined in color, merely touching the canvas with paint, even, when necessary, to paint with the canvas itself. With color applied in light, almost silken traces, Hakman recorded on the painting a synthesis known only to himself, based on specific painting punctuation — a code consisting of tiny greenish and pinkish-grey spirals by which he maintained a fluent dialogue with nature.

Cheerful landscapes of Dalmatia suited his sensuous nature. The exuberance of such landscapes and the abundance of natural light in them, creating a different scene with each of its constant changes, provoked always new moods in the artist. Hakman had the advantage of knowing how to watch, to truly feel nature and all the merely hinted impressions in the atmosphere and to enrich the painting with atmosphere concealing silver flickering of the air itself and the quivering sound of „An Afternoon of a Faun“ (Hercegnovi, 1933/34). Due to his great ease in painting and good mastery of the craft and, above all, his complete dedication to artistic creation, Hakman knew how to transform color into sound, to develop a musical sense in the painted values, to transform tones of color into melody.

That is why his light coloristic arabesque shaped by free Matisse-like gestures sounds like a „gigue“, while the rich colors of our Southern regions have the sound of „Roman Pines“. When Hakman, delighted by a motif, transforms reality into lyrical imagination and the sensuous gaiety of green shades radiates more strongly from within, than a simple landscape of calm configuration becomes a green sonic poem in which violet and white tones are equal to the movement of light (Burdocks).

While in painting landscapes Hakman remained faithful to the „local color“ and character of the scenery he was conveying onto the canvas, finding in them the general and significant features of the region and not just the characteristics of a particular motif, in the painting of interiors he strived to create an intimistic atmosphere of tranquility. That is why his intimate scenes with figures (A Woman Reading) or without them (Window) contain within them all the compositional and coloristic elements of French Intimistic Painting. His interiors are not made of „cadres“. They are spontaneously selected corners of rooms with no stressed compositional nucleus. In such, randomly selected areas, in which the author maintained an intimate dialogue with objects, the atmosphere of a natural ambient is created in which the figures do not pose but behave spontaneously: they work, bathe or rest. Although Hakman does not insist on the depth of space in these paintings two planes are visible on them: the first one determined as the „resume“, the second one as the background, most frequently a wall with window— open or shut—through which the city scenery can be seen. Whether the picture rests upon the value procedure, where the color is in the role of accent, or the color scheme of the painting is based on a more complex, more sonic register and freer strokes, it always bears a note of freshness, optimism and serenity.

A rich palette and more complex harmony of color are more frequent characteristics of Hakman's paintings in the period after 1936. This change from tone to colouristic painting seems to have the most logical flow in his paintings of still life.

If we exclude Still Life in Landscape painted during his stay in Poland, containing all the characteristics of Polish Impressionism and turn to his Still Life with Bread created four years later, we can see that Hakman was faithful to Cezanne's principle in the application of proceeding „realiser et moduler“ even then. The painting is Cezannistic by arrangement, modulated by precise relations of adequate tones, for „for when they are harmoniously arranged and complete, the picture forms entirely on its own“.

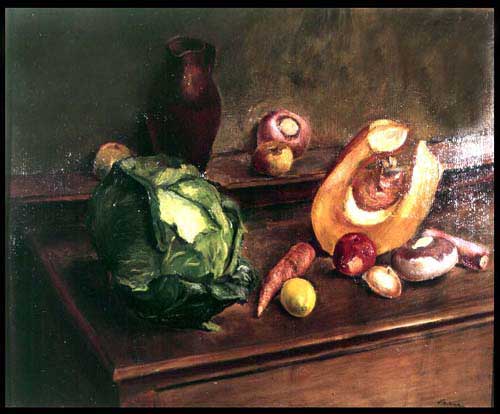

In 1930 Hakman painted his Still-Life with Cabbage with which he presented himself as an artist insisting on the materialization of objects and putting thought into the creation of a balanced composition. Objects are arranged in a rhythm flowing from left to right with alternating warm and cold, light and dark tones, contrasting in form as well. From 1930 onward, Hakman used more color in the painting of still life—at first cultivated Bonnard-like color of greenish, pinkish and yellowish tones (Still Life with Apples in Coffee Cups) or subtly nuanced violet and greyish-brown tones in formed

Floral shapes (Irises), and after 1936 he used a palette of rich coloristic register with a clear differentiation of color values of powerful sound, which in joining form pasty shapes resounding with fullness and freshness. The background is no longer neutral—surfaces ornamented with colored arabesque became an active participant in the composition (Still Life with Basket, Interior with Fruit) or was presented as a luxurious detail in a fabric lightly tossed across a chair, in a flower arrangement otherwise rich in color created with vibrant strokes (Flowers).

Still-life with cabbage, 1930

Similar freedom in proceeding and coloristic expression was exhibited by Hakman in his self-portraits made after 1936. It might be concluded that such a free treatment of colors is, in fact, the result of his refined feeling for colored sound. Colors are in mutual contrast or harmony (never mutually indifferent), creating the desired characterization of a figure and disclosing his state of mind (Self-Portrait with Palette).

In 1937 Hakman took part in a series of exhibitions. Three of them stand out, equally significant and interesting: two of them abroad—in Paris and Rome, the third in Belgrade, as the first presentation of the artists gathered in the group „DVANAESTORICA“.

At the World Exhibition in Paris in 1937, when, due to misunderstanding among the artists, the opportunity to display the work of Yugoslav artists, testifying of the unquiet years in Europe before the war, to the world together with Picasso's „Guernica“, Hakman presented his work with two paintings for which he received a gold medal. 51

At the exhibition in Rome, when Yugoslavia was the first foreign country to be presented at the newly-opened Roman gallery on the Square Colloni, and when an Italian art critic noted that, notwithstanding the apparent dependency on French art „certain individuals must be commended for their originality“, one of Hakman's paintings was bought for the National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome.52

Although it developed in several parallel directions, the main tone of Serbian fine arts during the thirties was marked by followers of the Colouristic and Intimistic Painting. Both received motivation from the same surroundings—from Paris. While the goal of the first was to rehabilitate color so neglected during the previous decade, the second group were for quieted art which, as Milan Kašanin wrote upon his first encounter with their art, „will testify to nothing but refined sensuousness and great culture“53.

A great number of Serbian artists took up realistic painting with poetic content during the fourth decade, causing a wide span of various creations to be made in such a style, where „color had the role of accent in the composition.“ Artists of the group DVANAESTORICA were the nucleus of this painting of Intimistic content; although the group had only two exhibitions, in the autumn of 1937 and the autumn of 1938, it left a strong mark on the entire Serbian painting of the thirties54.

On the occasion of their first exhibition, Milan Kašanin pointed out that the group consisted of artists brought together „by the similarity of temperament and equality of views“, and that it entered the artistic life of Belgrade „without advertisement and noise, without written programs and declarations ... and even without a catalogue“. „These artists“, Kašanin continues, „must have, first of all, a developed feeling for completion, for balanced creation of paintings and a sense of „reaching the end“, where no more and no less than intended is said and where the relations and links between feelings and artistic skill are perfect ... there is nothing improvised nor accidental“55.

The opening of the exhibition of the group DVANAESTORICA was followed by many comments in daily and periodical papers. Among the critics who wrote about the exhibition Pjer Križanić stood out with his conclusion that the exhibition was „rare in the uniqueness of artistic views, the love for color and the high level“, that „the only desire of the artists was to show that a European exhibition could be created in our surroundings by good selection, a combination of various artistic personalities and intelligent arrangement.“56 Jasna Pervan reached the same conclusion a year later when she wrote the following in her review of the second exhibition of the group DVANAESTORICA: „The exhibition transports the viewer to the Rue de la Boetie ... which is unavoidable if we remember that almost all contemporary painters found inspiration in Paris“; but she continues: „by more careful observation we can discover personality in each individual which the artists (further) interpret with a personal note of Parisian inspiration“, concluding, among other things, that „Hakman is a bit weaker in his nudes“57. This Nude from 1937 was directly inspired by Pierre Bonnard's painting Siesta. In the „tucked-in“ ambient of intimistic painting the foreground is occupied by a lying female nude of pink skin on whose body a subtle light, stirred by color, flickers. In the position of the nude, painted from behind, there is a suggestively accentuated relaxation and hedonistic ease. The scene is completed by a background painted in delicate arabesques with floral motifs scattered throughout the surfaces divided by verticals, skillfully achieving the balance of space. The picture Barefoot in the Garden is also full of the typical intimistic atmosphere; with impressionistic technique and fine blending of yellow, blue and greenish-brown tones Hakman created the transparency of pastel sound. The foreground of the picture contains a female figure in a sitting, slightly ex-centered but natural position, with a yellow hat on her head. Her clothes, as a coloristic dominance of the scene upon which the static balance of the painting lies, are contrasted by restless details laid out by Hakman in unusually buoyant handwriting. Those swift stenographic records, suggesting more than describing or defining the form, marked the intimistic serenity of the whole scene with a shiver of impressionistic excitement.

In September of 1938 Hakman was deeply stricken by the death of his brother Stefan: in him he lost not only his brother, but also his teacher and lifelong idol. He believed in his view of life and his attitude towards people, respected his judgment on values and believed in his objectivity and the best intentions of his writing about artists. „He knew that artists were in essence people quick to react to criticism“, Hakman then wrote to a friend of his, „and that a critique can frequently have a positive or negative influence on the creative work of an artist“.

Kosta's brother, Stefan Hakman

His brother's death might be the reason why Hakman painted little and exhibited rarely during the following two years, before the war started. He did, to be true, still take part in large joint exhibitions - the 13th Autumn Exhibition in 1940 was his last. The exhibition included 222 works of art, and therefore the general conclusion was that the „the space in the Art Gallery has become insufficient for joint exhibitions“; a critic wrote that Hakman's painting, A Woman in an Armchair „is consistently and softly created and deserves attention“ 58. In his opening speech dr. Jovan Radonjić said: „Our artists have worked and created in these difficult times of uncertainty and confusion in the world when, like almost never before in history, mankind wants to destroy the old to the very foundations“.

22. „Politika“, March 1, 1925.

23. Branislav Nušić, who was Head of the Ministry of Education at the time, gathered „prominent“ citizens around him in order to persuade them to do something for art and artists. The Association of Friends of Art „Cvijeta Zuzorić“ was founded. The association had a great role in the cultural development of Belgrade. Its members assisted the opening of the Gallery at Kalemegdan in 1928.

24. Among the paintings from that period, the most important ones were bought by Hakman's friend from Poland, Pavle Beljanski. He brought them for his own collection.

25. Boško Tokin, Šesta jugoslovenska izložba u Novom Sadu, Reč, Beograd, 1927.

26. Ibid.

27. Boško Tokin, Šesta jugoslovenska izložba u N.S., LMS, vol. 304, p. 108.

28. Exhibition of the „Manes“ group from Prague, Exhibition „Polish Print in XX Century“, an exhibition of French artists which included the works of Picasso, Leger, Robert and Sonia Delaunay, etc

29. Todor Manojlović, Izložba slika Koste Hakmana, Srpski književni glasnik, Beograd, 1929, vol. XXVIII, bn. 7, p. 464-466.

30. Gustav Krklec, Izložba slika g. Koste Hakmana u Umetničkom paviljonu, Život i rad, Beograd, July-December 1929, book IV, vol. 24, p. 957.

31. Members: Danica Marković, Sima Pandurović, Sibe Miličić, Ivo Andrić, Todor Manojlović, Mirko Korolija, Josip Kosir, Branko Popović, Milan Nedeljković, Ljubo Babić, Tomislav Krizman, Vladimir Becić, Milan Minić, Mihajlo Marinković Stevan Hristić, Miloje Milojević, Kosta Manojlović.

32. Menbers: Živorad Nastasijević, Vaša Pomorišac, Ilija Kolarović, Staša Beložanski, Radmila Milojković, Svetolik Lukić, Josip Car, Zdravko Sekulić, Branislav Kojić Bogdan Nestorović.

33. Branko Popović, Petar Dobrović, Jovan Bijelić, Sava Šumanović, Veljko Stanojević Marino Tartalja, Toma Rosandić, Petar Palavičini, Sreten Stojanović - Founders. The following new members soon arrived: Ivan Radović, Ignjat Job, Mihailo Patrov, Nikola Bešević, Zora Petrović, Milan Konjović, Mate Radmilović, Kosta Hakman, Stojan Aralica.

34: J. Objektivizam grupe „Oblik“, Politika, Beograd, December 17, 1929.

35. As reciprocity for the exhibition of British art. The initiative came from the Yugoslav Association in London.

36. See: Obzor, Zagreb, April 26, 1930, nb. 95.

37. By decree No. 6551, from July 23, 1930, he was appointed secondary school teacher in the First Male Grammar School. In a letter dated August 2, 1935, Dean Office of Technical University informs the Rector's Office that „Mr. Kosta Hakman, a superior teacher in fine arts, was appointed to that position in May 23, this year.“ Appointed by decree nb. 33535 from October 28, 1940.

38. Members: Mihajlo Petrov, Mladen Jošić, Ivan Čučev, Ivo Šeremet, Stanka Lučev, Kosta Hakman, Đorđe Andrejević-Kun, Risto Stijović, Anton Huter, Radmila Milojković, Staša Beložanski.

39. V. Izložba K. Hakmana i S. Stojanovića, Politika, Beograd, March 10, 1931.

40. D. A., Juče je otvorena izložba slika g. Hakmana i skulptura g. Stojanovića, Vreme, Beograd, February 1931.

41. Đorđe Bošković, Izložbe, Srpski književni glasnik, Beograd, February 16, 1931, vol. XXXII, bn. IV, p. 336.

42. John Rewald, Pierre Bonnard, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1948, p. 58.

43. Miodrag B Protić, Srpsko slikarstvo XX veka, I, II vol. Nolit, Beograd, 1970. Lazar Trifunović, Srpsko slikarstvo 1900-1950, Nolit, Beograd, 1973.

44. Bernar Dorival, Savremeno francusko slikarstvo, Svjetlost, Sarajevo.

45. N. J., Proletnja izložba u Umetničkom paviljonu, Politika, Beograd, May 17, 1932

46. Mirko Kuljačić, IV proljetna izložba jugoslovenskih umetnika u Beogradu, Razvršje, Nikšić, July-August 1932, bn. 3, p. 97.

47. —. Mlađi umetnici i prolećna izložba, Vreme, Beograd, March 31, 1932.

48. Ibid.

49. After Amsterdam, the exhibition was held in Brussels, in January 1933.

50. Đorđe Oraovac, Izložba slika g. K. Hakmana, Nedeljna ilustracija, Beograd, March 8 1936.

52. Ljiljana Stojanović, Catalogue for the Exhibition „Jugoslovenski paviljon na svetskoj izložbi u Parizu 1937“. Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrade, 1987.

52. The exhibition was organized by the idea of the president of Artistic Confederation, Pavollini.

53. Milan Kašanin, Izložba Dvanaestorica, Umetnički pregled, Beograd, November 1937, vol. 2, p. 59.

54. Members: Milo Milunović, Ivan Tabaković, Nedeljko Gvozdenović, Stojan Aralica, Borislav Bogdanović, Kosta Hakman, Hinko Zum, Milan Konjović, Peđa Milosavljević, Frano Šimunović, Risto Stijović, Franjo Kršinić. At the second exhibition, Zora Petrović and Marko Čelebonović joined the group.

55. Milan Kašanin, Izložba Dvanaestorice, Umetnički pregled Beograd, November 1937, vol 2, p. 60.

56. Pjer Križanić, I izložba Dvanaestorice u Umetničkom paviljonu, Politika, Beograd, October 16, 1937.

57. Jasna Pervan, Izložba „Dvanaestorice“ u Beogradu, XX vek, Beograd, vol. V, December 1938, p. 783.

58. Đ. O., XIII jesenja izložba u Umetničkom paviljonu „Cvijeta Zuzorić“.

©2003-2004 Project Rastko, TIA Janus (Belgrade), Hakman

family and other copyright holders.

No part of this site can be used or distributed without permission.