1941-1961:

The war and post-war years

In the concentration camp in Dortmund 1941-1945

The war years sharply divided the work of Kosta Hakman into two parts. A drastic cut was made by a time spent in the prisoner of war camp that he was taken to in 1941. Although he tried to spend the time there helping his friends by using his knowledge of the German language to protect them, or organizing painting courses for prisoners, Hakman was unable to endure the terrible camp ordeal. He was sent home very ill towards the very end of the war in 1944 with the transport of sick prisoners.

After the liberation, in 1945, when the Academy of Fine Arts began working again, Kosta Hakman was among the professors from the „old school“59. His students remember him as a conscientious teacher devoted to his calling, who taught his students honest labor. Apart from his pedagogic work, Hakman painted a lot after the war and exhibited frequently. He took part in all the exhibitions of ULUS, of which he was member since the founding of the association and in 1955 he held his fifth solo exhibition in Belgrade. Since his death in 1961, during the following two decades, three more exhibitions of his works were held, the last of them in the Portrait Gallery in Tuzla in 1980.

It is difficult for us to accept the fact that his postwar painting (oils, not aquarelles) is not a continuation of his pre-war painting, when Hakman was among the „artistic elite“ of Belgrade. We should bear in mind that it was more a change of handwriting than of subject matter which, to the contrary, remained almost unchanged in his opus that lasted for almost four decades.

Hakman's world remained that of objective reality in its visual representation, mainly the landscape that enabled him to develop the language of a poetic realist on that iconographic base. However, his postwar works do not have the spontaneity and freshness, ease and directness that was so characteristic for his earlier works. Although he remained faithful to the syntax of his prewar artistic work—the desire to express his artistic impression in an impressionistic palette, his work lacked the true the lyrical inspiration from the days of his youth — his postwar paintings were characterized by routine procedure. However, here and there, Hakman ignites the flame, particularly after 1956, when several of his paintings sound fresher, more organized. Several portraits have been preserved from that period, testifying to the fact that Hakman insisted on psychological determination of characters, forming the plasticity of the faces by clashes of color and light (Portrait of P. Gaćinović, Portrait of Pjer Križanić), and among them is an extremely successful portrait in the technique of pastel, A Portrait of Bora Radenković. Known as a man of great artistic erudition Hakman knew how to direct colorism towards expressionistic expression (Self-portrait) or to anticipate sound of the postmodern painting in clashes of intensely colored stains (Washing).

In the domain of aquarelle painting Hakman's postwar work was a logical continuation of his prewar painting. The spontaneous expression of subtle transparency and stylistic purity remained (Sunflowers, A Woman and a Child etc.).

Sunflowers, around 1955

Aquarelles represent a separate chapter in the artistic opus of Kosta Hakman. Painting in this technique, the transparency of which was based on the sound of a series of „aliquot tones“ and the fragility of which allows almost no corrections, Hakman made works of art that can be included among the best creations of Yugoslav aquarelle painting.

Hakman did not use aquarelle to color drawings (he used drawing as a means to carry out the analysis of form, to accentuate detail) and but rarely saw aquarelle as a sketch for some larger painting (however, he frequently painted the same motif in oil and in aquarelle). In his opus aquarelle was an independent discipline, sufficient unto itself. It was a completely formed work of art in which forms arose from dissolved color, mostly frequently devoid of graphic elements--lines and contours, which are a consequence of intellectual superstructure rather than the true state of nature. That is why aquarelle, as a medium of color, influences the viewer directly, since our eye, like in nature where there are no visible lines, notes only space and color. Even when he used a pencil, Hakman does so in order to fix an idea, to retain form or motion.

Since with Hakman the creation of an aquarelle is a result of direct observation, the means of swiftly recording coloristic sensations, aquarelle remains the most authentic witness of his artistic impression. Hakman knew how to keep each painted layer visible through the layers placed on top while preserving the white surface of the paper and its texture as an important factor of the painting.

Studying the artistic work of Kosta Hakman in whole, we may conclude that his aquarelles were created parallel to his painting in oil, that all changes in his oil paintings were reflected on his aquarelles, and that these two segments of his work are in a specific reciprocal relation. This was, after all, confirmed by the artist himself in his reply to the question of how he creates aquarelles: „the same way I create oil paintings“.

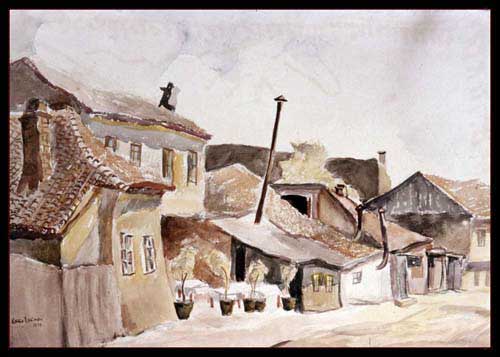

Just as he passed through phases of tone and coloristic painting with his oils, the transparency in his aquarelles was achieved both by the tone and the colouristic procedure. And while, in his works created by the principle of tone, he painted shapes as thick nuances that stand out from the warm basic tone (Skadarlija), Hakman, by the introduction of color, stirred light in the clear language of the aquarelle, permeated the texture of the aquarelle with it, making it bright and transparent (Still Life). For his aquarelles Hakman chose motifs such as interiors, still life or details of some old city quarter. Due to the selection of such topics and the procedure by which he realized them, he was able to develop in multi-layer treatment the poetics of the scenes of „cosy“ home ambience (Interior) or, by light play of brush, to create the atmosphere of the purest intimistic picture with transparent strokes (Window).

Skadarliya

With the simplicity typical for him, Hakman knew how to portray the roundness of an apple or the curve of a vase with aquarelle transparency, without neglecting their material characteristics (Still Life). He also knew how to use aquarelle as some kind of archive material to disclose the values of the dilapidated walls of hovels and valuable antiques, to use unerring transparent brush strokes to narrate and event with wit, to articulate it in space and time and attain factographic truth (Skadarska Street). In the aquarelle opus of Kosta Hakman there is particular charm in those aquarelles whose arabesque records motifs with ease (like in Dufy's pictures), at the speed at which the aquarelle dries, when, in fear of losing his thought, suggests more than he describes the scene (The Street). Aquarelle opened new possibilities in expressing the phenomena of color, light and atmosphere to his natural inclination towards landscape painting, and to his artistic sensibility for the ease of creating aquarelles landscapes were the most appropriate subject matter; mostly green, fresh and sunlit littoral landscape. Hakman knew how to turn such a landscape into transparent aquarelle, to make it airy and flickering, and to fill it with light to the very core. He managed to maintain a clear dialogue with it, like a simple thought or light conversation, both when creating aquarelles by clear coloristic stains (Ičići) and when he painting with whiteness, leaving great white surfaces of paper unpainted (Sea Landscape).

The work of Kosta Hakman in the domain of other painting techniques, graphics and drawing is almost negligible. Several preserved pastels testify to his brilliant command of this subtle means of painting, while several linocuts which he had made based on experience acquired in Krakow, since his professor Weiss was very successful in graphics as well; can be included in the general concept of his painting, above all by choice of subject matter (Flowers beside a Window, Orebić).

In his drawings Hakman presents himself as an accurate sketcher who mastered the basic elements of this discipline, although most frequently not in clear lines drawn „in one stroke“, but more often than not, contains the characteristics of a painting.

He died on December 9 1961 in Opatija, where he spent his last three years nursing a serious heart condition.

Beside his painting

In the rich opus of Kosta Hakman created during almost forty years of artistic work, we can distinguish five periods. However, such formal separation might sooner refer to temporal than to artistic and stylistic wholes, since the characteristic features of individual phases do not appear in clear form, but every period contains—as an aspect of retardation or anticipation—elements from both previous and subsequent phases. Therefore the phases in his painting cannot simply be termed „the Bonnard phase“, even when elements of intimistic poetics prevail, or „the Cezanne phase“, although the ideas of the master from Aix-eu-Provence dominate, for the changes that took place within each phase resulted in works of art with different visual solutions. This dichotomy in Hakman's work points out the artists sensuousness, his refined creative intuition to „mark a geographic notion, climate, geological formation“ with color…(Hyppolite Taine). If we did insist on defining Hakman's handwriting in individual phases, then the following could be said in the briefest possible notes:

In the first phase (1924-1925) the stroke is short, impressionistic. Strongly colored surfaces are lit by a natural, flickering light;

In the second phase (1934-36) the stroke is long and slow, in a palette of harmonious brownish-pink and grayish-olive tones, the light is of pearly sheen;

In the third phase (1934-1936) the stroke is more liberal, entwined, green tones prevail, with soft silvery light;

In the fourth phase (1936-1941), a vibrating stroke, color of strong colouristic sound, intense light;

In the fifth phase (1945-1961), procedures of impressionistic realism, carried out in a routing fashion.

Impressionist by method, sensualist by feelings, realist by attitude towards the world, Hakman based his art on a direct perception of the seen. He studied on the model of nature for as long as he lived, aware of the fact that „Landscape painters are as happy as hunters; they are in the open air, they sit anywhere - on the edge of a forest or near water, and finding interest in expressing themselves everywhere“60.

Adopting impressionistic aesthetics he accepted more its syntax than its essence—he starts from a pure impressionistic palette but subdues it and connects it by principle of tone. Exploring the possibilities of colors, Hakman lingered on green—from silvery-green to nuances of chromium— using it mostly in painting the semper virens landscapes of our coast, to which he constantly returned, finding in it the challenge for true artistic excitement, like Cezanne in the scenery with the Saint-Victoire hill.

Polish postimpressionism, in which French impressionism and Polish „hlopomania“ (obsession with themes from country life) are mixed with elements of ever-present symbolism, had a decisive effect on his work. It was the thread that Hakman never deserted, although, due to the ease of his painting, he constantly tested his artistic curiosity. Like a musician measuring or composing sonic values, he combined colors according to their gender in precisely measured intensity of light and in the exact place, since—„the laws of beauty in any art are inseparable from the specific qualities of its material and the technique applied“61.

His thematic repertoire is intimistic ... interior, still life or a section of a landscape; iconographically, his world is visually recognizable—real; semantically, Hakman's painting procedure rests upon the postulates of postimpressionistic painting. Although it might be said that his painting was influenced by French art in which he found confirmation for his painting affinities— mainly in the works of Cezanne and Bonnard, he formed his own handwriting, his manner of phrasing and visual punctuation, by which he proved that, in the work of an artist, the destination is less important than his interpretation.

59. Decree of the NRS 2055 dated April 5., 1945. Appointed full professor on April 29, 1950.

60. John Rewald, Cezanne, Abrams, New York, 1986, p. 73.

61. Eduard Hanslick, Vom Muzikalischonen, Leipzig 1910.

©2003-2004 Project Rastko, TIA Janus (Belgrade), Hakman

family and other copyright holders.

No part of this site can be used or distributed without permission.